(February 2016)

My former Hamilton College professor won the New Hampshire primary.

My former Hamilton College professor won the New Hampshire primary.

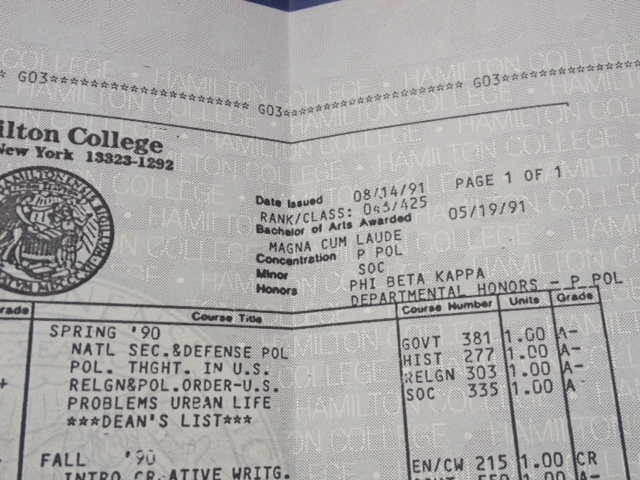

As an undergrad a quarter-century ago, I would have certainly told you that such a future outcome was as unlikely as Alexander Hamilton, himself, being the subject of a smash-hit rap musical. Today, "Hamilton" is the toughest ticket on Broadway and the guy who stood in front of my Sociology 335 class is making a pretty good case that he should be the next President of the United States.

I join the millions of Americans that Feel The Bern and support Bernie Sanders for President. A few recollections from my time as a student in Sanders' class underscore the reasons why I would love to see the man I once called "professor" be called "president" next January.

Bernie's Right

My course with Professor Sanders was titled "The Problems and Potential of Urban Life" and the classroom lectures were lively interactions between students, most of whom hailed from non-urban environments, and our former-mayor-practitioner professor. As one of the few in the class who actually grew up in a city, I was an active participant in in-class discussions and quite often challenged Sanders about his views by using examples relating to Philadelphia.

When I spoke excitedly about the active construction of the Pennsylvania Convention Center, I was surprised to find that he was not a fan of such a YUGE (as he might say) government subsidy for the hospitality industry. The investment, he said, was essentially a sucker's bet that would come at a hefty cost, but never pay off for most city residents.

Years later, conducting analyses for the Controller's Office, I was struck by the fact that, while the Convention Center's construction was supposed to spur the construction of many hotels to house conventioneers, hotel after hotel required additional public subsidies. Then, we were told that we would have to fund expansion of the Convention Center to generate more business for those hotels that we had to subsidize after the original Convention Center investment.

Sanders was right. Rather than invest in efforts that would create the conditions that would encourage economic development, we played a hunch, then had to double-down and triple-down on a bet that has paid out for some at a tremendous cost for the rest of us.

Bernie's Left

Professor Sanders described himself as a socialist mayor and there was never any question about his politics. But, far from offering left-wing demagoguery about the ills of capitalist America, Sanders focused his classroom lectures on people -- the real people who endured those problems and potentials of urban life.

Sanders required students to venture from our idyllic ivory tower atop Clinton's College Hill to the decidedly gritty, hardscrabble streets of Utica, NY. Coursework required us to meet with city officials and city residents as we considered the challenges of service delivery in a city enduring some of the worst effects of America's urban crisis.

When I hear now-Senator/Presidential-candidate Sanders speak about ensuring that no full-time worker lives in poverty; that every man, woman and child in our country should be able to access the health care they need regardless of their income; and that we must reform our political campaign finance system which is increasingly controlled by billionaires and special interests, I don't hear propaganda. I hear policies that will have a direct and positive effect on people's lives.

His was one of only a handful of courses in my undergraduate years that forced me to apply what I was learning in class to the real world. There can be no question that Sanders has a distinctly left-of-center political philosophy, but when it came to governing as a mayor and instructing as a professor, that meant that the focus was on people and the policies that could improve their lives.

Bernie's Centered

When he wasn't in front of his classes, Professor Sanders was focused on what would be his first successful campaign for Congress. He was not in the race to raise issues or to draw attention to policies. He was running to win.

I had an on-campus job working in the college computer lab where I would lend out software discs to students, un-jam dot-matrix printers, and remind users to save their work on back-up discs. (Each of these tasks must seem as ridiculous as "churning butter" to anyone born in recent decades). One of the more esoteric and mundane chores I had was to jump to attention anytime the giant tractor-fed printer behind me roared to life so I could tear off the printed pages and file them for pick up. It seems that this printer was connected to what we now know as the Internet, but back then, messages from afar would come to my printer addressed for a recipient who would then pick up the hard copy from me.

One day, Sanders appeared at my window rather excited to get something that had been spat out by my printer. Maybe it was polling or some other data. I can't recall the content, but do remember the message was so important that Sanders couldn't wait to review the material and had to splay the accordion-folded pages on my desk to devour the information. This was no quixotic quest. It was a real political campaign focused on data and intent on winning an election, not simply providing Sanders with a platform.

By the eve of the Iowa caucuses, the Sanders campaign received more than 3,000,000 contributions from more than 1,000,000 individual donors -- more than any other presidential candidate ever. The records for engagement, the statistical tie in Iowa Caucuses, and the win in the New Hampshire primary demonstrate that while technology has changed dramatically since Professor Sanders used my desk to review campaign data, this race is similarly focused on winning.

Berning Love

I had a chance to reconnect with my former college instructor before he hit the presidential campaign trail.

"Professor Sanders," I greeted him. "It's been a few years and a few more gray hairs for both of us, but you look great."

He gave me a close look, but showed no sign of any recognition. Sanders only taught two courses in 1990, but there was no reason to believe that my face would stand out 25 years later.

"I hope I gave you a good grade," he offered, as he moved to meet the next well wisher.

"You gave me an ‘A,'" I responded. "Now you give ‘em hell!"

I doubt I'll have another opportunity to get close to him, but I'm helping his campaign a little and pulling for him a lot. I learned much from Professor Sanders. I learned that for government to work best, policies must make sense for real people and I learned that for politics to make sense, elections must be about making real change not just offering positions.

Thank you, Professor Sanders, for teaching me that people always come first, and for sharing that vision with the country through your campaign.

My former Hamilton College professor won the New Hampshire primary.

My former Hamilton College professor won the New Hampshire primary.